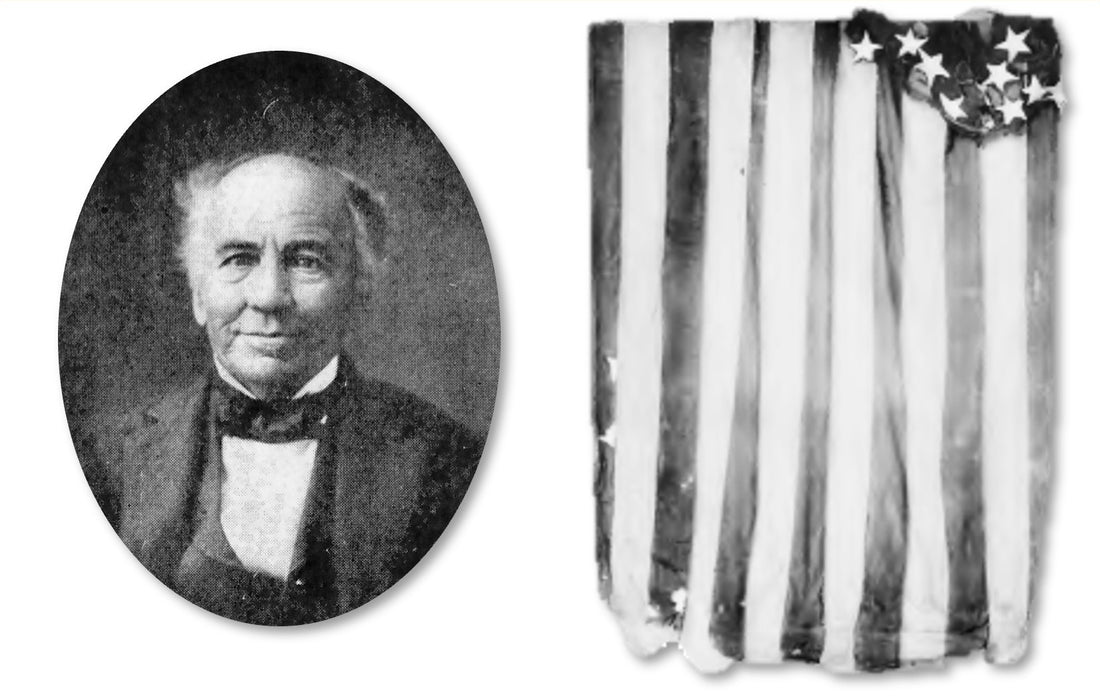

Old Salt of the Month - Captain William "Old Glory" Driver

This month, we Hoist our Mugs to Old Salt, Captain William Driver, who was born on March 17, 1803, in Salem, Massachusetts.

At age 13, Driver ran away from home to become a cabin boy on a ship. Then at 21, Driver qualified as a master mariner and assumed command of his own ship, the Charles Doggett. In celebration of this great achievement, Driver's mother and other women sewed a flag and gave it to him as a gift in 1824.

With this flag flying over his ship, Driver went on to have a colorful career as a U.S. merchant seaman, sailing to China, India, Gibraltar, and the South Pacific. In 1831, while voyaging in the South Pacific, Driver's ship "was the sole surviving vessel of six that departed Salem the same day." Driver picked up 65 descendants of the survivors of HMS Bounty and brought them back to Pitcairn Island. Driver was convinced that God saved his ship for that purpose.

With this flag flying over his ship, Driver went on to have a colorful career as a U.S. merchant seaman, sailing to China, India, Gibraltar, and the South Pacific. In 1831, while voyaging in the South Pacific, Driver's ship "was the sole surviving vessel of six that departed Salem the same day." Driver picked up 65 descendants of the survivors of HMS Bounty and brought them back to Pitcairn Island. Driver was convinced that God saved his ship for that purpose.

Driver was deeply attached to the flag. As tradition holds, he wrote on 10 August 1831, "It has ever been my staunch companion and protection. Savages and heathens, lowly and oppressed, hailed and welcomed it at the far end of the wide world. Then, why should it not be called Old Glory?"

Driver retired from seafaring in 1837 after his wife Martha died from throat cancer. At the time he was 34-years-old and had three young children. He settled in Nashville, Tennessee, and took his flag with him, flying it on holidays rain or shine. The flag was so large that he attached it to a rope from his attic window and stretched it on a pulley across the street to secure it to a tree.

Soon after Tennessee seceded from the Union, Tennessee's governor sent men to Driver's home to demand the flag. Driver, now 58 years old, turned the men away at his door after demanding they produce a search warrant. An armed group returned to Driver's front porch, at which time Driver refused to produce the flag, saying "If you want my flag you'll have to take it over my dead body."

To save the flag from further threats, Driver and some of his neighbors sewed it into a bed spread and hid it until February 1862, when Nashville finally fell to Union forces. Driver went to Tennessee state capitol after seeing the U.S. flag and the 6th Ohio's regimental colors raised on the Capitol flagstaff and asked to see the general in command. Horace Fisher, the aide-de-camp to the Union commander, described Driver as "a stout, middle-aged man, with hair well shot with gray, short in stature, broad in shoulder, and with a roll in his gait." Introducing himself as a sea captain and Unionist, Driver brought the coverlet with him and opened it, revealing the flag. Nelson accepted the flag and ordered it run up on the Capitol flagstaff. The 6th Ohio later adopted the motto "Old Glory."

One night, a violent storm threatened to tear his flag, so Driver replaced it with a newer flag, taking the original Old Glory from the 6th Ohio for safekeeping. The flag remained in his home until December 1864, when the Battle of Nashville was fought. As Confederate troopers under the command of John Bell Hood sought to retake the city, Driver hung the flag out of the third-story window and left to join the defense of the city. For the rest of the American Civil War, Driver served as provost marshal of Nashville, serving in hospitals.

On July 10, 1873, Driver gave his flag to his daughter, Mary Jane Roland, telling her "This is my old ship flag Old Glory. I love it as a mother loves her child. Take it and cherish it as I have always cherished it; for it has been my steadfast friend and protector in all parts of the world—savage, heathen and civilized."

What happened to the flag?

Well, following Driver’s death a family feud erupted over the ownership of the flag. Driver's niece, Harriet Ruth Waters Cooke, the daughter of Driver's youngest sister, said she inherited the flag and presented her version of Old Glory to the Essex Institute in Salem, which became the Peabody Essex Museum, along with family memorabilia that included a letter from the Pitcairn Islands to Driver. Cooke published a family memoir in 1889, omitting any mention of Mary Jane Roland. Almost two decades later, Roland wrote an account of the flag, publishing Old Glory, The True Story. In that memoir, Roland disputed Cooke's narrative and presented evidence for her claim that the flag she owned was the true Old Glory. In 1922, Roland gave her Old Glory to President Warren G. Harding. Harding had the flag sent to the Smithsonian Institution. The same year, the Peabody Essex Museum sent its Old Glory to the Smithsonian. The Roland flag is generally accepted as the authentic Old Glory, as it shows signs of having been flown at sea and is considerably larger than the Essex flag.